Why don't you go back?

NYCDensityMapper, Pt. 2 - Discussing Manhattan

Using the NYC Density Maps I developed and walked through my creation of in my previous post, I give some thoughts on the patterns--and the changes that should be happening--in Manhattan's density.

Maps

Midtown's Black Hole

SoHo - A Tale of Two Districts

East Side Story

The Maps

NYC's residential density mapped by the block level.

About those Blocks...

Back to Start

Midtown's Black Hole

We've all seen it on the street: it's 5 PM. Office workers, hedge fund managers, CEOs, and interns alike walking down 6th Avenue, finding the nearest ten-dollar coffee store or subway entrance. You think, wow, this place really is the financial capital of the world...... if you're a tourist, that is!

Jokes aside, despite being known for its lively business activity in the day, the office district of Manhattan, which comprises this part of Midtown:

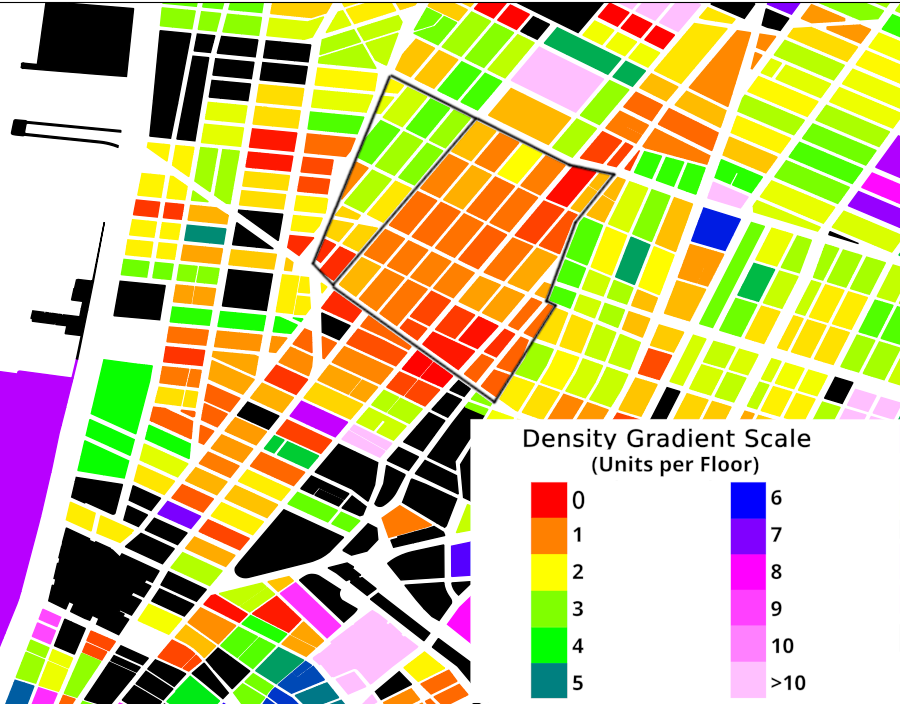

is quite dead after the standard work day is over. Come past midnight, and it is almost a dead zone. As Andres Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk pointed out in Suburban Nation, having a city be active 24 hours a day, aka be a "24-hour city", is essential to economic and social health, and round-the-clock safety, aka self-policing, which is honestly something we could all use more of in the US. Unfortunately, the housing density of this commercial district looks like this:

A near black hole of housing density in what should be New York's densest region.

As housing is essential to maintaining a 24-hour city (no city can ever function round-the-clock if people aren't living there, with some very very specific exceptions like gambling districts or airports), Manhattan's office district is very heavily at risk of being a ghost town at night. Bars, restaurants, and clubs can only be open for so long, usually themselves only until 1 or 2 AM.

In order to bring this very core area of New York back to life, it is imperative that new housing be offered here, of course, at a wide range of price points to support a diverse economic mix. Especially following the COVID-19 pandemic, many office spaces are sitting around unused, unsold, or worse yet, completely undeveloped. As husks of buildings sit empty and undeveloped in the middle of Manhattan's most prized section of real estate, while people are sleeping rough on the street right outside, one wonders if this is some kind of practical joke.

Thankfully, there has been incremental movement towards housing in Midtown's office district in recent years, especially seen in the Grand Central Area. The Office of the Mayor of New York City has posted a statement on rezoning and redeveloping Midtown's, and other boroughs' office districts for housing, which is ultimately good.

From the Statement:

"The Office Adaptive Reuse Task Force was convened by the Adams administration in July 2022 following Local Law 43, sponsored by New York City Councilmember Justin Brannan. The task force’s recommendations include: Expanding the universe of office buildings with the most flexible regulations for conversion to residential use from buildings constructed through 1961 to those constructed through 1990 — easing the potential conversion process for an additional 120 million square feet of office space... Finding opportunities to allow housing, whether through conversions or new construction, in a centrally located, high-density part of Midtown that currently prohibits residential development..."

Hopefully this will bring about a quick change to many of the failing 24-hour neighborhoods of New York City, giving them the housing opportunities, and the night life that they deserve.

Back to Start

SoHo - A Tale of Two Districts

Beautiful SoHo, the land of transplants, rich tourists, NYU students who don't know any better, and buildings that cost millions to own. After all, it is the vaunted Cast-Iron Historic District! What else could you expect? Except what if I told you that there was a cheaper way to own or rent some of these buildings' spaces with almost the exact same interior quality, with identical buildings, identical street culture, in the same exact neighborhood? You would call me insane, until I told you about an interesting part of SoHo you may have never heard of. Here's why this is the case.

Let's start with a strange pattern I noticed in the density map in Lower Manhattan.

In Soho, the West Broadway street serves as a sort of barrier between two zones of density, with blocks east of it having housing densities between 40-80 units per acre, and blocks west of it having housing densities between 100-200 units per acre. What we're essentially seeing is a 150% increase in density just by jumping one block. You might be wondering: "These two blocks must have different types and sizes of buildings, right?"

Take a look at this shot of West Broadway, and tell me which side is which.

If you couldn't figure it out, don't worry. Neither could I, until I pulled out Google Maps to see which way was north. (FYI, the left side is the denser one)

Generally, both sides of this street feature buildings with mixed use, four-to-six story buildings, classic architecture styles, including the historic cast-iron style, and a calm, yet lively atmosphere. No, in order to see what makes these two sides of SoHo so different in density, one will not be able to discern anything from the outside of the buildings. We will instead need to look inside of them.

Let's consider some possible differences on the inside of these otherwise identical buildings that may lead to differing densities, especially differences with a factor of 2.5. Starting off, the difference in first-floor business presence, while possible, is one: not played out in reality, as both sides have healthy amounts of first-floor commerce, and two: negligible were it real, since whether all four-to-six of the floors of a building are used for residential purposes or just three-to-five cannot make a difference any larger than 50%, and that's being generous.

The only difference that can make such a big impact as the one seen along West Broadway is the quantity of units per floor. While not often talked about, units per floor can be a helpful measure of density on a building-to-building scale, as it can help us figure out how efficiently builders and landlords choose to parcel out the space inside of a given building.

To confirm this suspicion I had on units per floor, I slightly modified the code of my density mapper to track the average units per floor of all buildings in a block instead of just the average residential units per block. Instead of the raw unit per floor value per building, I calculated the average over an entire block with the number of floors factored in, in order to account for the number of units per floor of large buildings, or large complexes of buildings that took up one lot, appearing as one "building" object. Instead of biasing the unit per floor count in favor of larger buildings, this takes into account the number of floors and buildings in every lot in a block, giving fairer, and more importantly for us, comparable results in seeing what makes the SoHo border tick.

Here's what that modification looks like in SoHo:

As you can see, the split in density once again follows West Broadway, and it highlights the core differences between these two parts of SoHo: the number of units per floor of a given building. Blocks east of the border have buildings with around 1 unit per floor on average, while blocks west of the border have buldings with around 2-3 units per floor on average. What this means is a 2.5x difference per floor density. If you remember that number appearing somewhere else, good job! Your short-term memory is better than mine!

We can safely account for almost all of the density difference between these two parts of SoHo using this difference in floor plan. How exactly did the floor plans become so universally segregated? And what exactly does this mean for you, potential SoHo renter? (I mean seriously, have you please considered living somewhere else? You cannot really be this desperate to live in SoHo that you're reading some nerd's density blog about it, right?)

We must look at the zoning and politics behind the two historic districts that make up SoHo in order to understand this. That's right, there's two of them. The vaunted Cast-Iron district has a quiet twin brother: the Sullivan-Thompson Historic District. The border of these two districts is, of course, West Broadway. These two districts matured in very different ways from their inception.

When these two areas were built in the early 19th century, they followed very different trajectories. Sullivan-Thompson became known for its high population of Italian and African-American immigrants and densified the existing rowhouses to support multiple families per floor as needed.

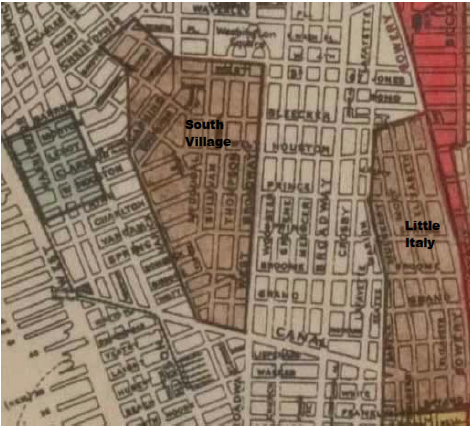

A 1920 map of Manhattan shows the major hub of the Italian neighborhood of the South Village (now Sullivan-Thompson) and Little Italy. It ends to its east at West Broadway. (Source)

Meanwhile, the Cast-Iron area became known for its high quantity of industry, and later, intense crime. The older, wealthy residents of the area, who moved in before many of the cast-iron buildings were made, fled. The population slowly dwindled into the 20th century, and it became barren of life and basic services. In truth, only recently did this area become known for any sort of population presence. As young people and artists illegally moved into this area during mid-century for its large open spaces (remember that one unit per floor thing?), it slowly became a region of wealth and power once more. They even won their rights to legally live there by modifying the zoning code, and successfully fended off an attempt to build an expressway through their neighborhood. This triumph of redevelopment of an industrial area spawned what we know now as "gentrification", although there weren't many people living there prior to the wealthier artists at the time to "push out", so to speak.

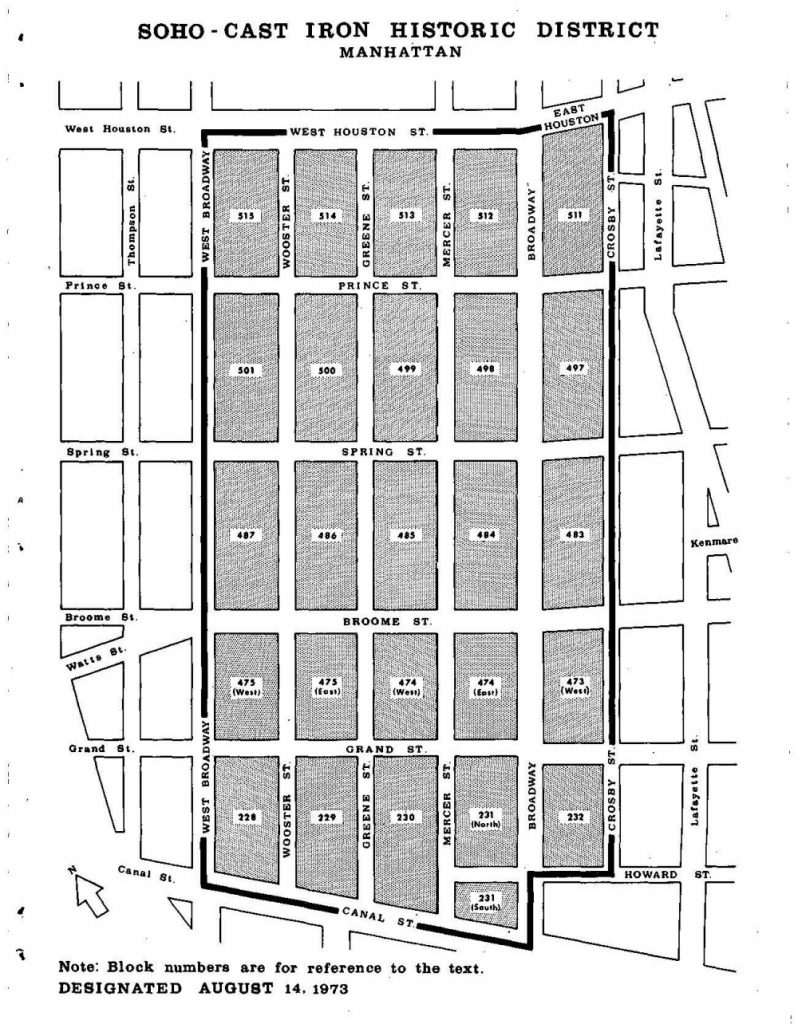

A 1973 map of the Cast-Iron Historic District, as it was being drawn up. It ends to its west at West Broadway. (Source)

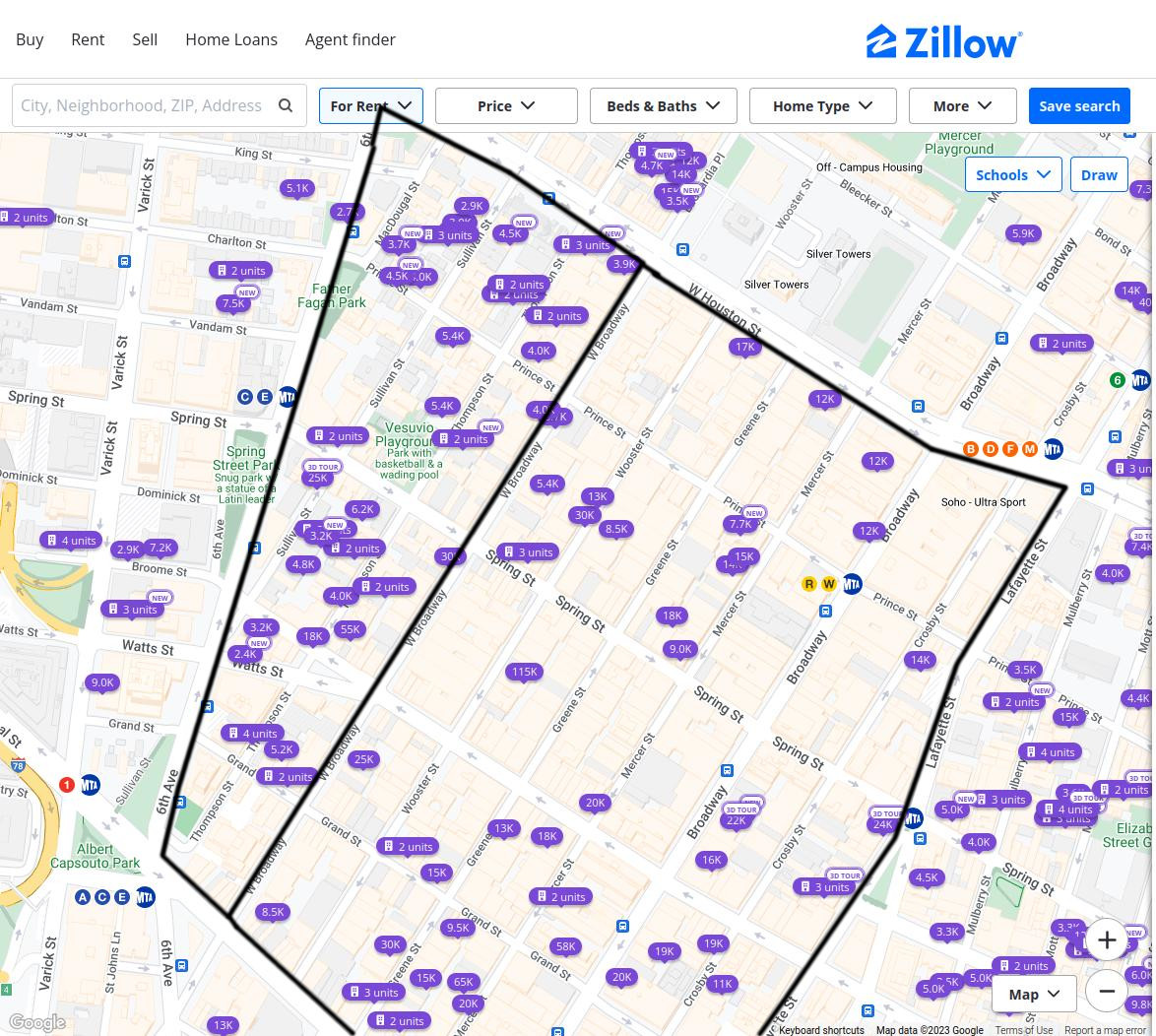

This triumph, as it goes without saying, is very limited, as many who have seen triumphs of the wealthy can attest. Most notably, the living space of these buildings has not changed from the "large and lofty" type that the original artists moved into, while the neighboring immigrant area of Sullivan-Thompson had split their spaces to fit more families. In 1973, the artists' district had been "Cast in Iron", so to speak, as their newly-passed historic district essentially prohibited any modifications to these buildings, even if they involved slightly modifying the inside of the buildings to support multiple families, without touching the, I will admit, beautiful exterior. Forever locking the relative sparsity in place, the Cast-Iron remains one of the most exclusive and unaffordable places in Manhattan, and it is almost directly tied to how spacious a single unit is. Comparing dense Sullivan-Thompson to sparse Cast-Iron in online rental listings (I used Zillow here) shows us how this affects the needs of regular New Yorkers who are looking for housing.

With the exception here or there, units in the Cast-Iron district range from 10 to 30 grand a month to rent. (If I wasn't in Macaulay, the tuition at NYU would have been cheaper than this.) Meanwhile units in the Sullivan-Thompson district range from two and a half to seven thousand a month to rent. While still expensive to be sure, this represents a four-fold decrease in rent prices, along with a MUCH greater availability of units than in the cast-iron district, despite it being a much smaller district in area.

While the cast-iron aesthetic definitely plays a role in the price difference here, it is obvious that the density and size of these units is also doing some heavy lifting in determining price, as supply of units heavily affects price just as demand for fancy iron buildings does. Another obvious fact is that this does two things for income inequality in New York:

-

It segregates who can live where. If there is no slow gradient or mix of unit types between cramped apartments and lofty floors, there will inevitably be a segregation of incomes. This is more obvious, and more serious, across Manhattan and NYC than it is in just SoHo, but SoHo is a great example as to how this can take place even in what people often perceive as an exorbitantly expensive or wealthy area. A single block can successfully separate the middle class from the ultra-wealthy.

-

It limits access to better served areas from those with less means. While Harlem is ripped apart from the Upper West or East Sides in an explicitly racial and evil manner, with many residents from the former never dreaming of affording the latter, it is a shame to imagine that all one needs to be able to afford a nicer apartment in a better served area, like the Cast-Iron district is now what with their boutique clothing shops and fancy restaurants, is just better zoning.

Densifying the Cast-Iron district can drive prices down by increasing supply, making it easier for less wealthy people to also be able to live in such a posh area of Manhattan. This is what I call "reverse gentrification", poor or working class folks moving into and improving the economic diversity of an otherwise inaccessibly wealthy area. This has been shown numerous times in sociological studies to be the best way to handle those who live in concentrated poverty: deconcentrate the poverty. Richard Rothstein's Color of Law best demonstrates the positive effects of this type of program in the example of Maryland's 1995 HUD Lawsuit, which resulted in the following:

"Successful civil rights lawsuits have led to a few innovative programs that integrate low-income families into middle-class neighborhoods. In 1995 the American Civil Liberties Union of Maryland sued HUD and the Baltimore Housing Authority because as these agencies demolished public housing projects, they resettled tenants (frequently with Section 8 vouchers) almost exclusively in segregated low-income areas. The lawsuit resulted in commitments by the the federal and local governments to support the former residents in moving to high-opportunity suburbs. The authority now funds an increased subsidy, higher than the regular Section 8 voucher amount, to families that rent in nonsegregated communities throughout Baltimore County and other nearby counties. Participants can use their vouchers in neighborhoods where the poverty rate is less than 10 percent, the population is no more than 30 percent African American or other minority, and fewer than 5 percent of households are subsidized. The mobility program not only places voucher holders in apartments; it also purchases houses on the open market and then rents them to program participants. It provides intensive counseling to the former public housing residents to help them adjust to their new, predominantly white and middle-class environs. Counseling covers topics such as household budgeting, cleaning and maintenance of appliances, communicating with landlords, and making friends with neighbors.

Those who have participated in this Baltimore program left communities with average poverty rates of 33 percent and found new dwellings where average rates were 8 percent. In their former neighborhoods, the African American population was 80 percent; in their new ones it is 21 percent." (Rothstein, 209-211)

Instead of rich folks driving out poor folks by shooting rents into the sky, like what is ironically happening in Harlem, let's pay realtors and building owners to split up these SoHo buildings into multi-unit floors, subsidize renters who will rent apartments in the new units, and watch those prices fall.

That being said, this change will not actually introduce THAT much economic diversity. No working class person can afford even Sullivan-Thompson present-day rents; SoHo will always be SoHo, but this can be used as a good example for densification projects in other, more suburban areas of NYC and elsewhere. Also for the most part, if people who already live in the larger SoHo units want to keep them, they are more than welcome to. They will also not experience significant real estate drops in their existing property, only price drops in for sale or for rent spaces where they have been densified. However, let's say real estate values DO drop (which they won't):

Concerns of the rich and their property values are mostly moot and inexcusable when many of them are perfectly comfortable doing the exact OPPOSITE to their poorer neighbors: renting cheap apartments, jacking up real estate values, and the most insidious of them all, watching poor people lose their homes because they cannot afford to live there anymore.

Let's stop pretending that rich people losing their real estate values is equally as bad as poor people losing their homes.

In sum, while its solution is NOWHERE near enough to fix the housing and housing affordability crises, the situation belying the two districts of SoHo shows how arbitrary housing price differences are. While this can be bleak, it is also a positive message in some way: we can just as arbitrarily lower these prices by reintroducing density into the equation. Densification almost always allows for greater affordability. Towards that end, there is a more exceptional tale I must tell...

Back to Start

East Side Story

The Upper East Side, fancy apartment towers, sophisticated museums, and a lovely park on its left side. What's more to love, and what's more to dream about being able to afford? In truth, the Upper East Side is actually more than a quiet retirement home for urban socialites, as there is once again another half yet discovered. Similarly to SoHo, one can find a strange split in density between the two parts of the Upper East Side.

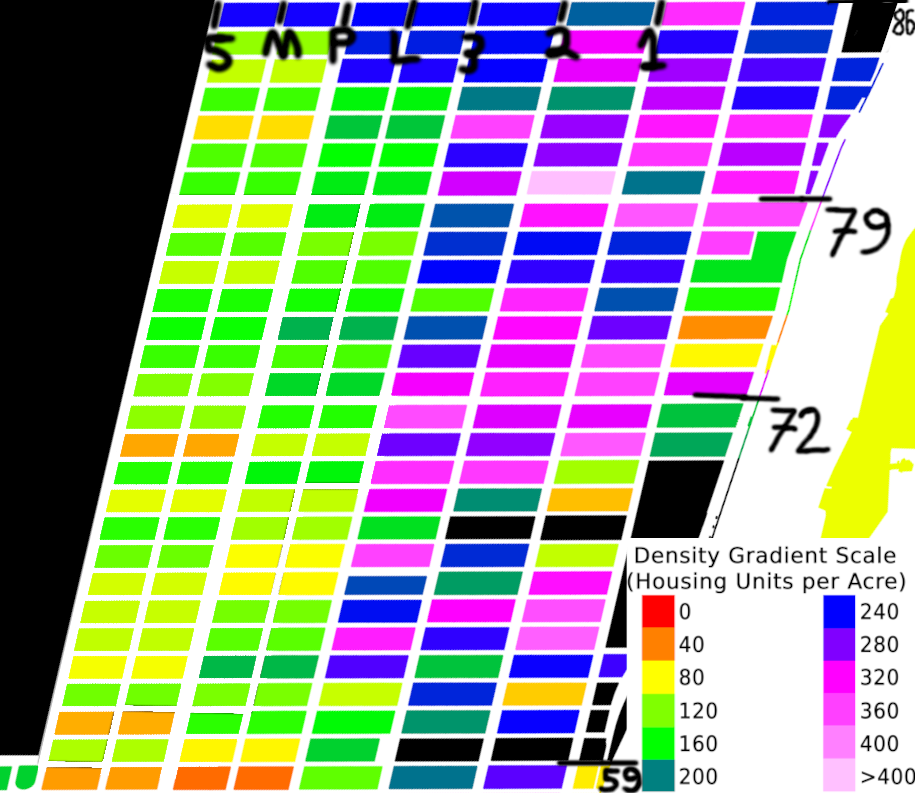

As shown on the map, what we're essentially seeing is a 100% increase in density just by jumping one block. Once again, one street, 3rd Avenue in our case, serves as the defacto border between two differing regions of density. Though the orientation is reversed, the story is the same. West of 3rd Avenue, and especially below 79th Street, the housing density is around 100 to 180 units per acre on average. East of 3rd Avenue, and especially below 79th Street, the housing density is around 220 to 360 units per acre on average. You once again might be wondering: "These two blocks must have different types and sizes of buildings, right?"

Here, things are a little more clear. Try to guess which photo is from the UES west of 3rd Avenue (we'll call this WUES for convenience), and which photo is from the UES east of 3rd Avenue (we'll call this EUES for convenience).

If you guessed that 1 was EUES and that 2 was WUES, and that you thought this was comically easy, you'd be double right! The built environment of these two parts of the Upper East Side are VERY different. While WUES has a consistent, uniform building height of around 12-16 stories, EUES is sporadic and chaotic in its building heights, with buildings ranging from three to a whopping 50 or more stories tall. The tallest of these is a Trump building at 69th Street and Third Avenue with an astonishing 55 stories (just a few blocks from my campus!). This was no accident. Much like in SoHo, this difference in density was the result of deliberate zoning decisions. UES took it up a notch by adding political and zoning battles that represented an over decade-long war between history and density, preservation and pushing limits, neighborhood leaders and real estate, NIMBYs and YIMBYs.

Let's quickly make something clear. As we're going to see later, the border between skyscraper EUES and uniform WUES isn't clear cut, and it's definitely not always going to be 3rd Avenue. The reason it appears this way on the density map render is because of a limitation in the categorization of blocks in New York City's zoning code.

The block between 5th Avenue and Park Avenue, Madison Avenue, and the block between Park Avenue and 3rd Avenue, Lexington Avenue, were built through Manhattan a while after the original 1810 grid plan in an attempt to boost retail potential on the east side. This resulted in two new up/down avenues, new buildings, and eventually led the way for the Lexington Avenue Subway decades later. However, all of this progress in Manhattan's street system was never picked up by the taxonomy of NYC's zoning code, which to this day refuses to recognize these two new avenues as legitimate separations between blocks, instead treating 5th to Park and Park to 3rd each as one super long block.

A representation of two sample blocks in the Upper East Side according to NYC's zoning code. Madison and Lexington Avenues fail to separate these two blocks in the code, and thus they stretch across from 5th Avenue to Park Avenue, and Park Avenue to 3rd Avenue respectively.

My program takes this data, lack of specificities and all, and produces a map of density by the block assuming that Madison and Lexington don't exist. Any changes in density between Park Avenue and 3rd Avenue are muddled out and the average is taken. If the density between Lexington and 3rd on a given block is double that of one between Park and Lexington on the same cross-street, the map will regardless show the two blocks as equally dense, because they are considered the same block by the NYC zoning code.

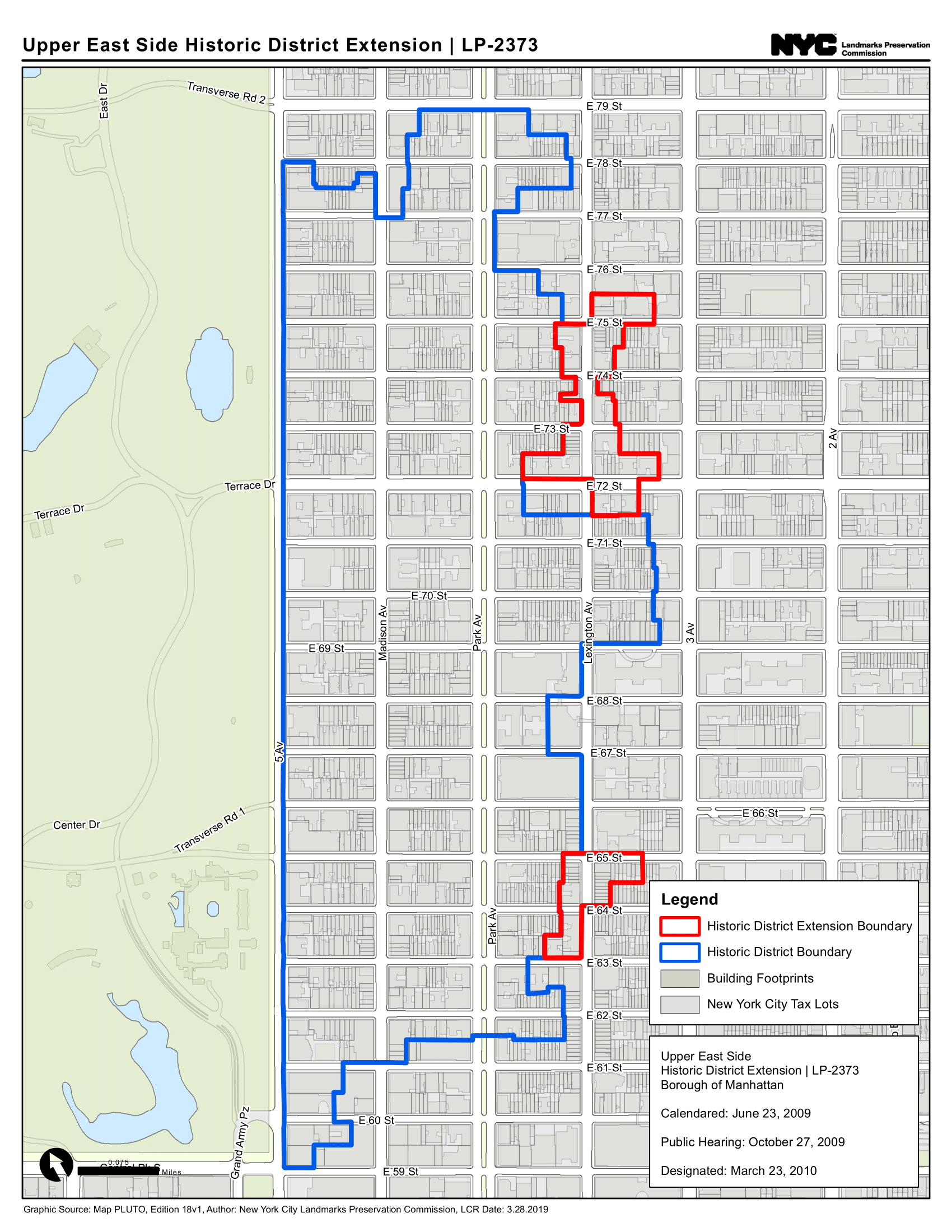

This is important to keep in mind as we head to the reason why EUES and WUES are so different, that being the Upper East Side Historic District.

This is the up to date map of the Upper East Side Historic District, with its 2010 expansion. It stretches to Lexington from 61st Street up to 69th Street, and straddles mid-block between Lexington and 3rd Avenues from 69th Street up to 76th Street, before retreating back to Lexington for its last three blocks uptown. As you can see, the eastern boundary of the district varies depending on the cross-street, so just saying "3rd Avenue" as the boundary does not do this complex border justice. Saying that the border is "somewhere between Park and 3rd Avenues" would be more accurate, which is why Lexington Avenue can vary greatly in character depending on where one is located in the Upper East Side.

This district was first considered for establishment in 1979, and was passed in 1981, with a national registration in 1984. During the 1980s, while the district was just finishing up making its way through the legal pipeline, development of apartment buildings in the EUES was reaching higher and higher into the sky. With the recent establishment of this historic district in the WUES, all of these buildings were built in the EUES, mostly east of Lexington Avenue, in order to get permits. Historic districts generally have very restrictive rules on what can or cannot be built, including buildings that would actually match the older style of the neighborhood, for fear of "copying" the classic architecture. With the character of the WUES locked into place, and following new zoning regulations for the EUES in the early 80s that were more permissive to tall, imposing towers, development was encouraged to flood into it, with buildings reaching into the thirties and forties of stories as housing demands continued to push the neighborhood into the sky. As a result, densities in the EUES crept ever upward, far outpacing that of the WUES.

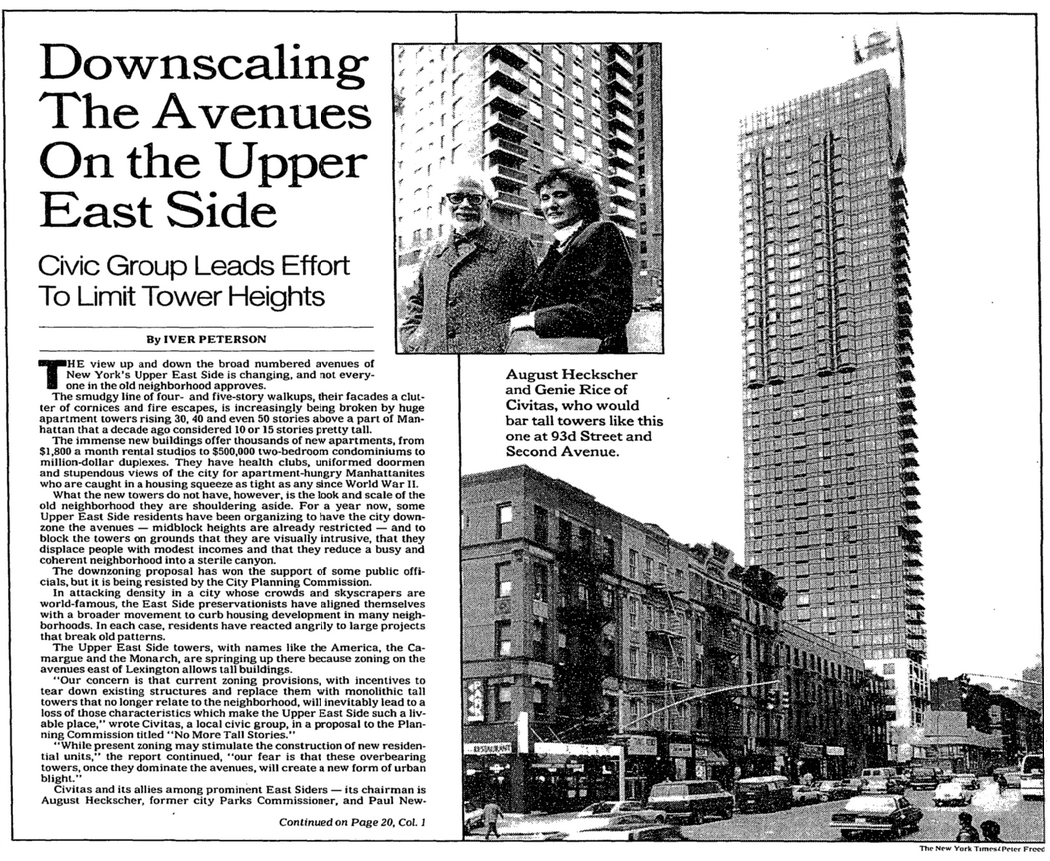

As the late 80s approached, the rapid construction of towers reached a breaking point in city planning politics, with two major belligerents: the NYC Planning Department and Real Estate Board, who saw the need for more housing and continuous upscaling in the EUES, and grassroots neighborhood preservation groups like Civitas, who felt that the new towers were antithetical to the character of the UES, and that their construction would greatly damage the neighborhood.

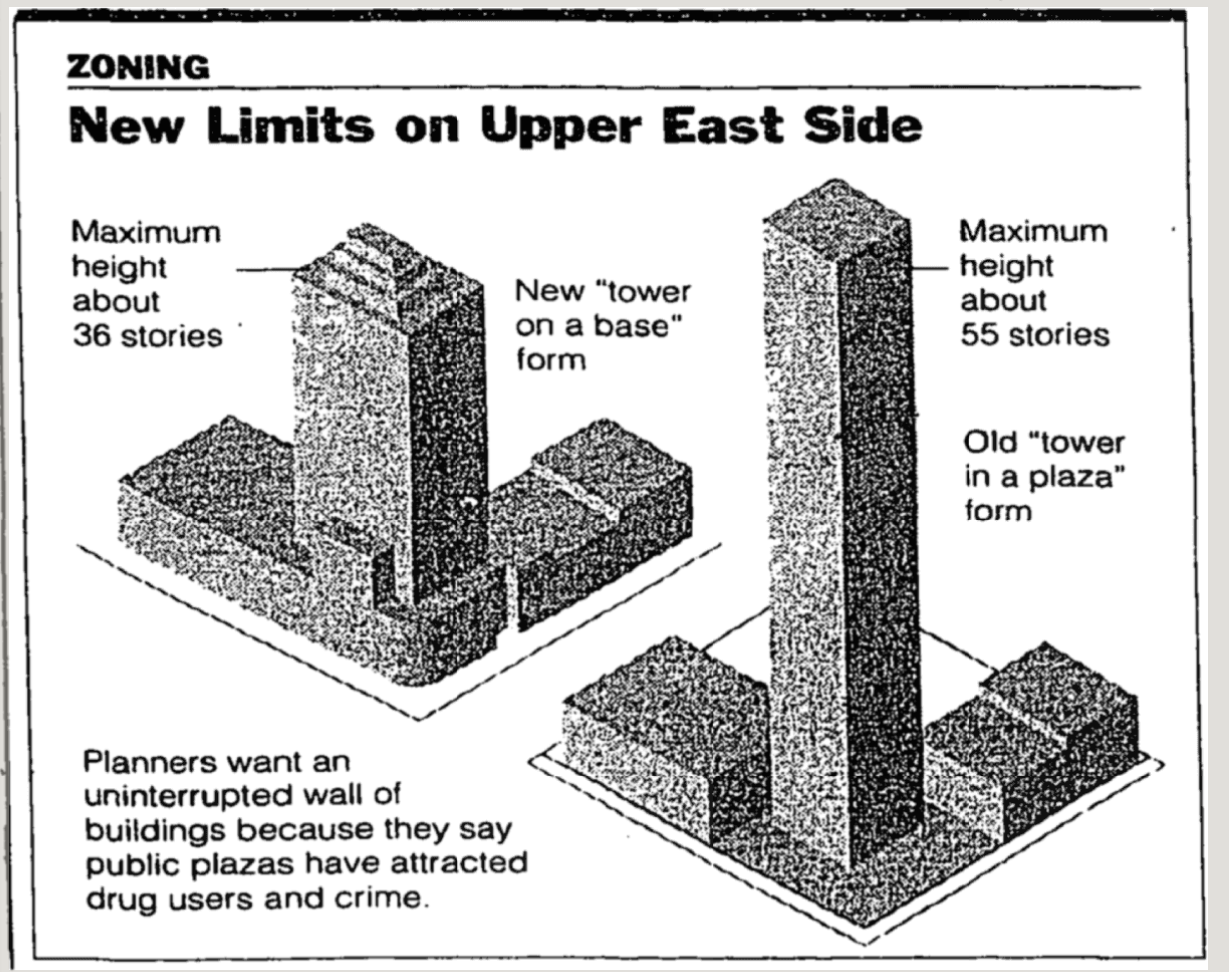

1986-87, Civitas Opposition to Supertalls, Pictured by the New York Times

According to a New York Times article on the matter published at the height of the conflict, the battle went somewhat like this:

The New York City Planning Comission sided with the real estate interests who wanted to build denser, taller buildings in the EUES, where they claimed demand was unignorably high, and where it was actually possible to build such projects, given that the WUES was protected from change. Civitas, run by August Heckscher, a former NYC Parks Comissioner, Paul Newman, and president Genie Rice, both disputed the legitimacy of these claims and argued that the real estate projects would damage the character of the neighborhood in a number of ways. For one, old business owners and residents would be pushed out from their homes and places of work, as real estate developers would gobble up neighboring buildings in order to combine their air rights into their lot, and build up as high as possible. These projects would also displace people on an economic basis, as the buildings were seen as exclusively luxury housing, which would push out poorer renters as the average home price would begin climbing. They were also outraged at the poor land use of these buildings on the street level, often giving way to parking, driveways, and private parks that the public could not use. Especially problematic to them were plazas at the entrance of the buildings, which, when built, allowed buildings to be even taller, but did nothing to improve the public space. Storefronts would be forgone in place of fancy entrances. All of these would, according to them, reduce the quality of life of residents and pedestrians.

In order to mitigate the effects of what they saw as a detriment to their neighborhood life, Civitas produced a proposal that would, among other things, reduce the maximum floor area ratio (FAR) from 10-12 to 9, and force buildings to adhere to the structure and integrity of the street by bringing the building fronts back closer to the sidewalk, removing private plazas, and introducing pedestrian-friendly storefronts. They recommended a UES-wide (both WUES and EUES) building height limit of ~20 floors, and setbacks mid-block after several stories in order to maintain the impression of a smaller building and preserve sunlight coverage. They also suggested to reduce the length to which mid-block buildings can be as tall as the ones along the avenues from 125-150 feet to 100 feet. A video essay was published by them in 1986 detailing these same points, with some visuals and an explanation by Paul Newman himself, entitled "No More Tall Stories".

Real estate interests, the planning commission, and the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, a conservative-libertarian political think tank, responded to these concerns by saying that these buildings do in fact mitigate the housing crisis in a economically just way, because there are a wide range of price options at which to rent or buy spaces in these buildings. Additionally, the Manhattan Institute argues forth the "trickle-down" theory of housing: if wealthier people had more options for living, that would free up the housing they are already consuming for poorer people to move in. They cite Co-op City as a positive example of this effect, where 15,000 people left Grand Concourse and other neighborhoods of the Bronx to move there, leaving more space for poorer people to move in.

Civitas clearly understands good urban design principles, and respects good architectural design, but the planners and the developers weren't necessarily wrong for building taller buildings. It would be fair to say that these taller buildings with the added regulations on form that Civitas suggested would be appropriate.

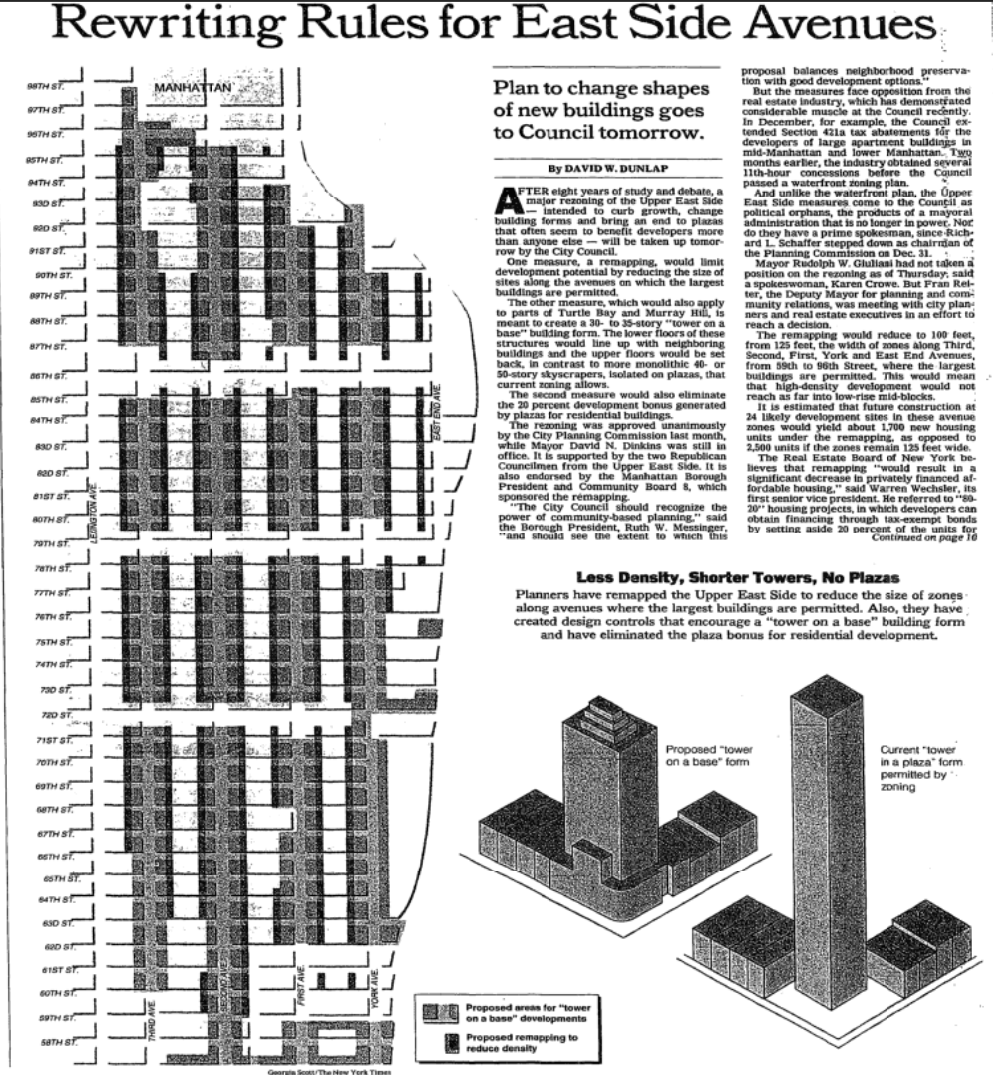

The course of city politics eventually came around to the same conclusion. According to another New York Times article, a few years later, the City Planning Commission began to work with Civitas on an alternative style to the new towers that were being built, one that would be more compatible with the neighborhood. Although followed by some minor disagreements on the midblock-to-avenue height break point (Civitas wanted 100 feet, the real estate sector wanted 125 feet), the Commission was able to put together a somewhat unifying plan on a new building code released in 1992 that would continue to be refined for another two years. The article quotes Civitas president Genie Rice saying as much, "It brought all the parties together at a place that was neutral."

New 1994 Proposal for EUES Zoning, Pictured by the New York Times

Yet another New York Times article documents the passage of this new EUES zoning code. In February 1994, the code passed unanimously in the New York City Council with a vote of 45-0, according to the transcripts (page 27) from the February 9 meeting . Between 59th Street and 96th Street, from 3rd Avenue to the East River, 35-story height limits, setbacks, storefronts, requirements to be flush with other buildings in the block, plaza bonus eliminations, and many more were passed. This, along with rules stipulating that 60 percent of floor space be concentrated in the first 15 stories, which encourage a "layer-cake" building structure, helped to re-establish proper urban design in the EUES zoning code without outright removing density and tall buildings from the equation. Buildings like the aforementioned Trump tower would after this point become illegal to build. This triumphant compromise between Civitas and the Planning Commission came with much chagrin to the New York Real Estate Board, whose president, Steven Spinola, was attributed by the Times as saying "the revisions will discourage new buildings, not only by reducing their allowable size, but by compelling builders to construct longer and darker apartments of less value." Let's investigate this claim after 30 years of Civitas-assisted EUES development.

It’s important to mention that the changes in zoning that took effect after 1994 did not mean that the old, imposing towers of the 80s got demolished. They remained as part of the EUES landscape, just as the older four-six story buildings were part of the original landscape. What did change was the building pattern that would continue into the future. Speaking to the concerns of the Real Estate Board at the time of the new zoning code's passage, numerous tall towers were constructed since then, and continue to be constructed up until the present day, all of which follow the code originally proposed by Civitas.

New 1994 Standards for EUES Zoning, Pictured by the New York Times

With some example buildings from around the EUES area, I will demonstrate the positive effects of the new building code, especially when compared to the old code from the early 80s, which produced, in my opinion, some of the most hideous buildings New York has ever seen. I took all of these photos at night, and for a few reasons. Most importantly, if one wants to know how truly safe and inviting a building is, one must see it do its work at night. Only an outstandingly safe, inviting, and interesting building can truly have people call it home at night. If a building is only vaguely active in the day, it may not be known how truly terrifying it is to be there at night. Secondly, it is a little easier to see lights, restaurant outings, and open stores at night, with their bright bulbs flashing to pedestrians: "I'm open!". This difference in ease of activity measurement between night and day is, well, night and day. I went around between 8 and 9 PM for these photos. Four major factors we will look at are building height, storefront presence, setback presence, and where the building falls on the spectrum between gaping plaza and flush with the sidewalk. The following categories generally emerge from these factors:

Short

Short buildings in the EUES, those that are under eight stories tall, almost always have storefronts, are flush with the sidewalk, and are too short to need setbacks in the first place. As a result, they fit in so well with the rest of the neighborhood that they are usually the epicenter of nightlife, usually having a restaurant storefront with outdoor dining. People are laughing, drinking, eating, and walking in or near these buildings with impressive ease, and why wouldn't they? This is the historic infrastructure of the EUES.

Two shorter buildings on 78th Street behind 2nd Avenue with lively commerce. Both built in 1910.

A set of six shorter buildings on 2nd Avenue between 77th and 78th Streets with lively commerce. All built between 1900 and 1920.

Old Tall with "Plaza"

Super tall buildings in EUES built before 1994 with plazas are usually so recessed from the sidewalk that they cannot have any meaningful commerce take place. Because of this, I saw a double whammy of uninviting buildings not just with no commerce, but also with plaza designs so terrifyingly brutal that they look like they're straight from a horror film. This is obviously compounded with the fact that they look ridiculously out of place with the rest of the built environment due to their continuous and unending height. I almost never felt safe here, especially since I went to take these photos at night.

The 40-story Knickerbocker Plaza Building on 2nd Avenue between 91st and 92nd Streets. Built in 1975, it provides difficult to access, sparse commerce, and breaks the continuum of urban space.

Old Tall with no "Plaza"

Super tall buildings in EUES built before 1994 without plazas fare a little better than their recessed counterparts. They are usually, but not always, lined with storefronts, making them more safe and inviting. However, there is still a nagging feeling of being under a cliff, as these buildings almost always lack setbacks. They are also still disjointed with other, shorter buildings in the area.

A 37-story tall tower on 2nd Avenue between 73rd and 74th Streets, built in 1967, flush with the sidewalk and has commerce, but is still imposing.

A 21-story tall tower on 2nd Avenue between 73rd and 74th Streets, built in 1964, flush with the sidewalk and has commerce, but does not seamlessly connect to neighboring buildings.

New Talls

Newer tall buildings in the EUES, which as you'll see, are mostly built after 1994, are required to have numerous things, including the aforementioned 35-floor height maximum, the setbacks, the flush nature with the sidewalk, and the availability of a storefront. Such regulations facilitate better integration with the surrounding neighborhood.

New Tall without Store

Usually these new talls with missing storefronts are simply in the process of renting out retail space, and sit in the meantime with brightly lit, empty first floors. This, while not preferred to a building whose lobby is lined with paying store managers who can offer rich commercial experiences, is MUCH preferred to the older style of super-tall development. There is also still a path to having commercial activity in the near future.

A 30-story tall tower on 2nd Avenue between 80th and 81st Streets, built in 2019, with the 1994 zoning code's setbacks, height limits, tight sidewalk space, and room for stores at the ground floor. It fits better with the other buildings thanks to the setback.

New Tall with Store

These new talls are truly the best of all worlds, tall and dense, but without interrupting the sidewalk or the view. They also provide commerce and retail to pedestrians and helps keep the street front active and lively. These buildings have the potential to, and often do, perform as well or better than the traditional short buildings at providing an interesting environment with fun activities.

A 32-story tall tower on 1st Avenue between 91st and 92nd Streets, built in 2004, with all the benefits of the 1994 zoning code. It fits seamlessly with the other buildings thanks to the setback, and it has a gourmet market on the first floor.

A 31-story tall tower on 2nd Avenue between 76th and 77th Streets, built in 2000. It also benefits from the 1994 zoning code, and has a TD Bank on the first floor.

Though these buildings can be anywhere between 25 and 35 stories tall, they still feel like a building with a lower height of around five-ten stories, and that is specifically because the setback successfully set up an illusion to the pedestrian that the building ends at that height. This allows for a more flush, uniform "wall" against the sidewalk, to use Newman's words. We have accomplished the feel of a cozy, inviting neighborhood, while simultaneously building taller, and providing high density for those who need the housing. The issues of sun coverage, adequate airflow, and wind management have been solved as well, as these "layer-cake" buildings block less sunlight and air, and are more compact and aerodynamic than the monolithic, unrestricted towers of mid-century through the early 90s.

Quick mention that there are still more new talls being constructed to Civitas standards in the EUES! This is 250-252 East 83rd Street on 2nd Avenue! At time of writing, it has almost been topped out, and is slated for opening in Fall of 2024.

Just thought it would also be good to mention that affordability, while maybe not attributable to any one style of development, be it the early 80s zoning code or the 1994 code, almost always rises with density, and we can see it here in the UES as well.

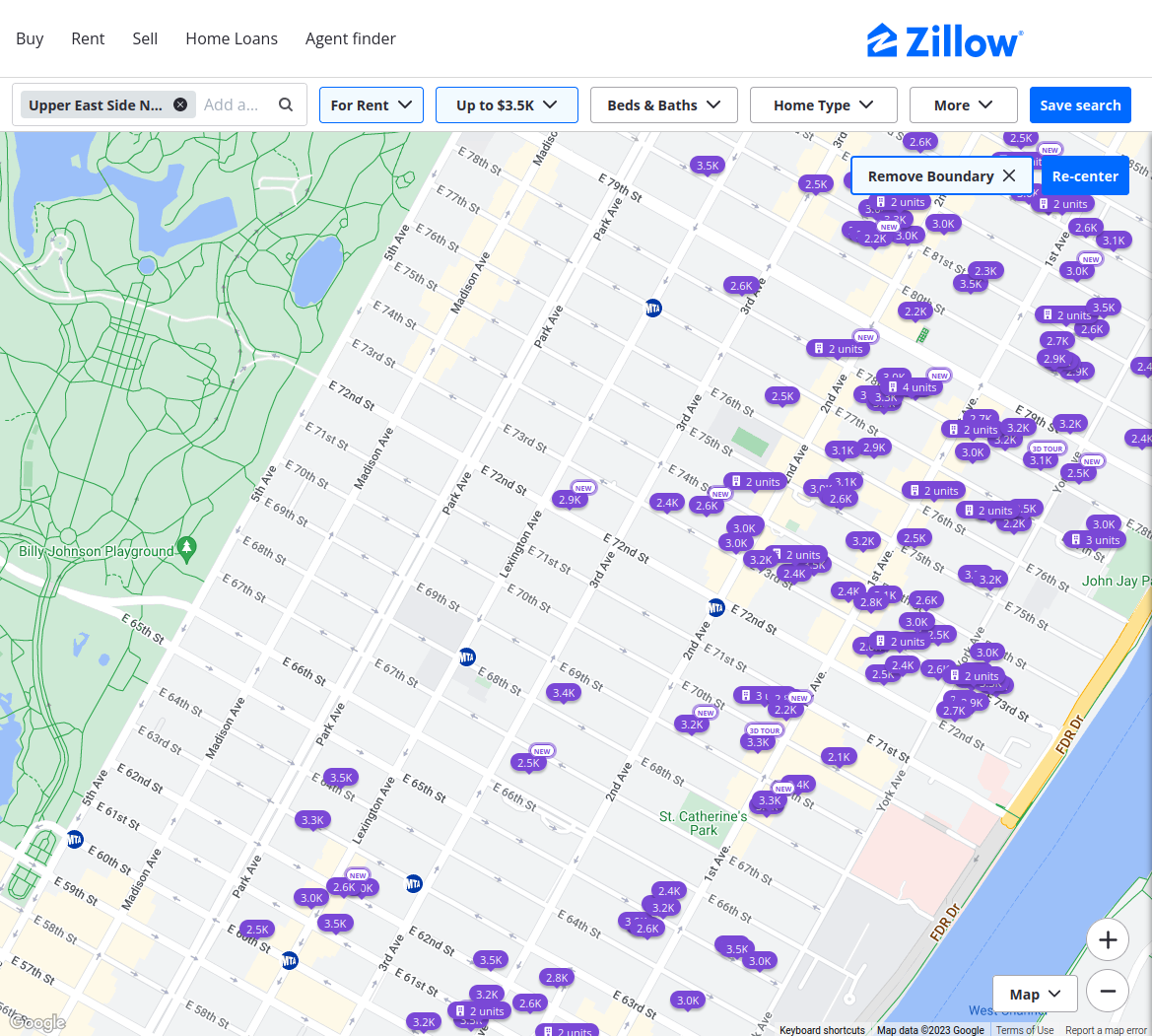

This Zillow screenshot shows that there is not a SINGLE unit for rent in the WUES, the historic district, that is below $3,500 a month. In comparison, the EUES has plenty such units. While living in the EUES is certainly not cheap, it is possible, which cannot be said of the WUES. I am not arguing here that we should in any way replace the historic district of the WUES with a laissez-faire free market capitalist free for all like the EUES was before 1994, but it is something to consider. Not every neighborhood in NYC can afford the burden of historical significance, and certainly many should be allowed to thrive in the modern day.

To that end, Civitas and the NYC Planning Commission, although they vehemently disagreed and argued on the methodology, they ultimately made their compromise in the mid-90s and decided to work together to build a modern EUES. They decided that density was important, but they also understood that blindly building towers without thought is not the proper way to do so. Civitas made sure that the zoning code carefully reviewed tower plans for neighborhood continuity, aesthetic merit, reasonable height limits, useful and engaging public space on the ground, and continued affordability and fiscal success.

I believe there is a firm lesson or two in this story. The voices of grassroots movements are immensely important in city planning decisions, especially when they represent a wide range of interests, not just those of the wealthiest or the most powerful. There is also a need for greater government oversight in making sure that we build responsible density. We must not create another hotbed for war like that which went down on the Avenues of the Upper East Side.

(Hey, did you know I made a montage of the Civitas video? Well now you do! Check it out here!)

See my takes on density in the other boroughs in my next few posts! Stay tuned!